Until now, I haven’t watched the cinematic juggernaut Nezha. A film about a rebellious, fire-wielding boy-god, defying fate in a swirl of animated spectacle—so I’ve read. The headlines tell me it has smashed records, soared past the billion-yuan mark (it has become the first Chinese film to gross 10 billion yuan), and cemented itself as one of China’s highest-grossing films.

But here’s what I find even more fascinating than the movie itself: not everyone who watches it seems truly moved by it, and yet they return, ticket after ticket, filling theater seats over and over again. For what?

To push Nezha to the top of the charts and break world records.

This act of rallying behind Nezha is more than just national pride—it reflects a broader pattern in Chinese consumer culture, where spending is driven not just by personal preference, but by the need to validate and elevate symbols of identity. This same phenomenon plays out in luxury consumption.

In recent years, this collective enthusiasm for homegrown culture has only intensified. The pandemic cut Chinese consumers off from overseas luxury shopping, prompting them to turn inward. This shift in focus on domestic culture reached a high point when the Spring Festival was officially recognized as a UNESCO cultural heritage, further fueling a wave of cultural nationalism.

In a recent piece I wrote for Vogue Business in China, I explored how this has fueled an intangible cultural heritage (非遗) movement in China—not just as a marketing tool for luxury brands seeking to localize, but as a genuine shift among young Chinese consumers eager to engage with their own cultural roots.

This shift reminds me of a conversation I had recently about China’s luxury consumers—what compels them to spend?

Yes, for one thing, they have the money. Decades of rapid economic growth have produced a generation of consumers who are not only wealthy but financially literate in ways previous generations were not. They have been meticulously groomed by global marketing machines, seduced by aspirational branding, and conditioned to understand the notion of luxury—its history, its craftsmanship, its allure.

Chinese consumers did not always have this level of discernment. It was learned, accumulated through years of exposure to omnipresent messaging from brands that sought to educate as much as sell.

But there’s something deeper at play. Beneath the gloss of Hermès silk and the polished leather of a Birkin, beneath the meticulous rituals of skincare and the diamond-encrusted whispers of high jewelry, lies a fundamental human desire: the need to be recognized.

Luxury in China is not just about ownership—it’s about participation.

The way fans of Nezha buy tickets not necessarily for personal enjoyment but to elevate the movie’s status is strikingly similar to the way China’s luxury consumers engage with brands. The act of buying is not only transactional; it is a performance, a statement of allegiance. To buy luxury is to belong—to a class, to a narrative, to an imagined ideal of sophistication and global citizenship.

But there’s another layer to this evolving landscape: Chinese consumers have become hypersensitive to respect. Years of interacting with global brands have made them acutely aware of whether they are truly valued—not just in service quality but in cultural representation.

A dual-track strategy—one approach for China, another for the West—no longer works. Consumers now scrutinize how brands behave across different markets, monitoring inconsistencies between their messaging on Chinese and Western social media.

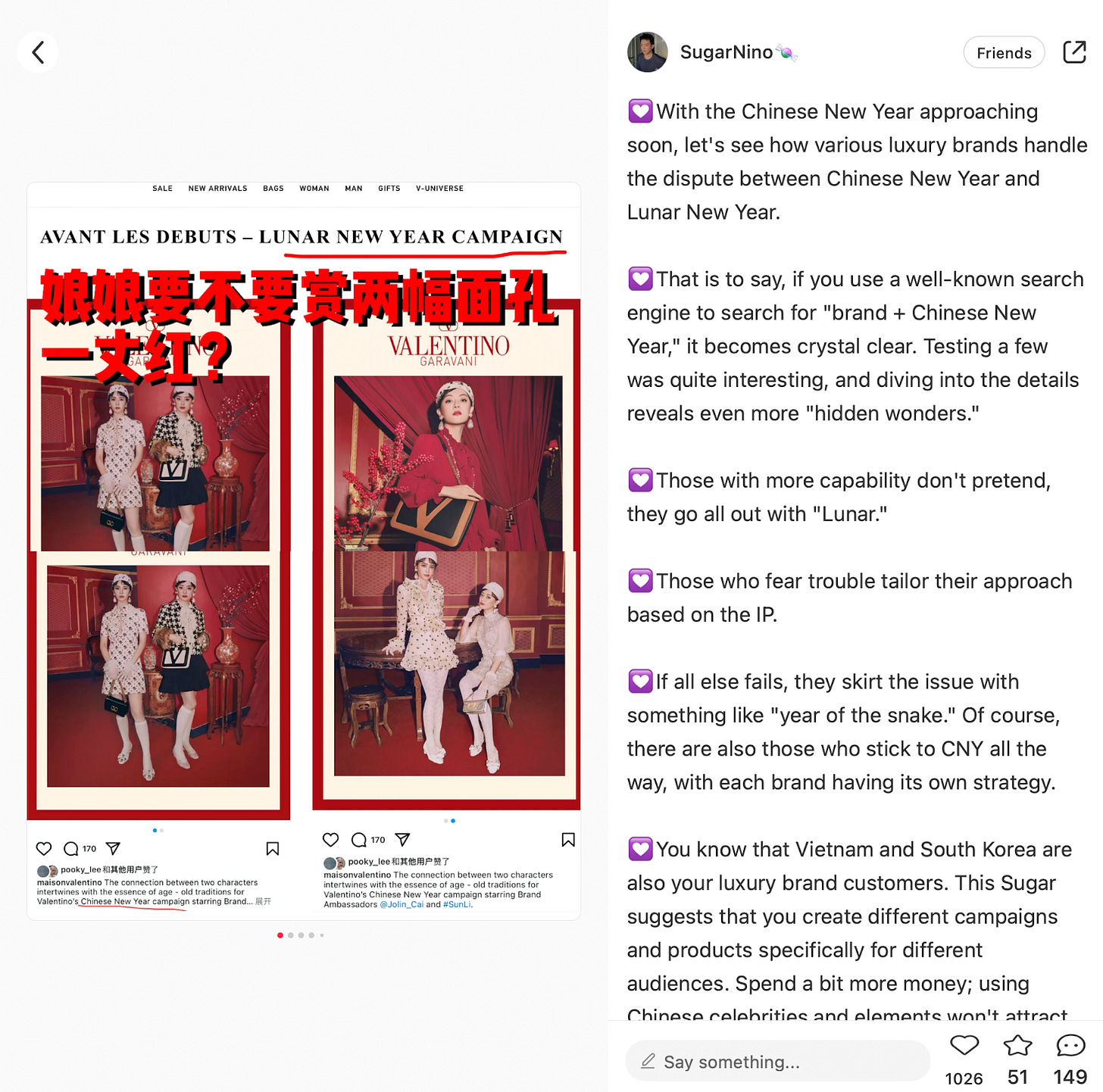

Take the Lunar New Year vs. Chinese New Year debate, for instance. On Xiaohongshu (also known as Red), users like @SugarNino dissected how luxury brands positioned the same campaign differently: Valentino was criticized for calling it Lunar New Year on its official website but using Chinese New Year elsewhere. Miu Miu, in contrast, subtly adjusted the phrasing based on different regional sites.

More recently, Fendi found itself under fire when it was accused of mislabeled the traditional Chinese knot as a Korean knot in an Instagram campaign. This kind of brand “fact-checking” has become increasingly common, and consumers are not afraid to call out double standards.

And yet, the Nezha phenomenon hints at a deeper cultural shift. The fact that consumers are rallying around a Chinese film—not purely for personal enjoyment but to elevate its status—mirrors the evolving dynamics of luxury consumption. For decades, luxury in China was about signaling wealth in its most literal sense. But today’s consumers are more nuanced.

They chase meaning as much as they chase price tags. They seek validation not just from their peers, but from the brands themselves. They want more than just exclusive products and premium services—they want brands to demonstrate a deep understanding of their culture, not just as a marketing tactic, but as a fundamental part of their strategy.

I mean, for sure, there is still room for international luxury brands to grow in China, particularly among high-net-worth individuals (HNWIs), who continue to value prestige, status, and exclusivity—even as homegrown brands gain traction. However, this may not hold true for the younger generation. They are increasingly skeptical, questioning the very foundation of luxury itself: Why should the West be the one to define what is luxurious and what is good?

Recognition, respect, acceptance—these have always been at the core of why we spend. The question is: as China’s luxury consumers evolve, will their spending power remain in service of external validation, or will they one day turn that energy inward, championing their own cultural capital the way they’ve rallied behind Nezha?